- Home

- Species & Infections

- Rhodotorula Mucilaginosa

Rhodotorula

mucilaginosa - The Fungal Opportunist

Updated 3/18/2025

Written by Dr. Vibhuti Rana, PhD

The Rhodotorula species, including Rhodotorula mucilaginosa are a sturdy fungal species that can stay viable for decades, even when stored in river water. The infections caused by the species of genus Rhodotorula are neither very frequent nor very ancient. After being reported once in 1960, they were quite infrequently reported in the subsequent years. Later, they were again reported after a long gap in 1985 (1).

These ubiquitous basidiomycetous species of yeast have been isolated from multiple sources of the environment like terrestrial plants which are decomposing in soil, marine settings, lakes, coastal waters, deep-sea waters, and igneous rock aquifers. Since they are quite resilient and tough in nature, they have also been found in extreme cold and acidic environments such as the ice glaciers of Greenland and Antarctica (2). It has been shown to absorb iron (III) ions in aquatic environments and can exist easily in waters that are moderately contaminated by the iron (III) ions (3).

What’s more, the presence of Rhodotorula in stools samples indicates that they can even survive the acidic gastrointestinal environment (4). This epiphytic yeast has also been found as a part of the normal microflora in the human feces, skin, sputum, and digestive tract of human subjects (5).

In humans, three species of Rhodotorula are considered to be infectious and lead to mild or severe cases of fungemia. These are Rhodotorula glutinis, Rhodotorula minuta, and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa (also known as Rhodotorula rubra). Out of these three, R. mucilaginosa is the most frequent etiological agent of infection in immunocompromised individuals. This species of Rhodotorula is specifically characterized by its inability to assimilate nitrate and d-glucuronate. However, it can assimilate glucose, maltose, trehalose, and raffinose. Another feature of this species is that it flourishes at 40°C - 104F. In terms of ancestral relationships, it is most closely related to R. dairenensis and R. pacifica.

To avoid misinterpretation in identification of this species from other related microbes of the same genus, molecular typing methods like sequence identification and analysis of ITS (Internal Transcribed Spacer) or D1/D2 (D1-D2 domain of the large-subunit ribosomal RNA gene) regions are required (6). In addition, mass spectrometry is now widely recognized for clinically relevant species identification. These methods always work more efficiently when compared to the conventional microscopic or biochemical tests for yeast species identification; and are quite trustworthy too.

The R. rubra or R. mucilaginosa colonies are mostly coral pink, smooth or reticulate, rugose (wrinkled appearance), moist to mucoid. Besides, they exhibit spherical to elongate budding yeast-like cells or blastoconidia which lack pseudohyphae or hyphae (7).

Many studies have emphasized the role of microbes and their aggregation in the formation of house dust particles. Along with Cryptococcus diffluens, R. mucilaginosa is the most common microbe found in house dust. It is believed that the most common reason for the occurrence of indoor fungi is food spoilage, which then contributes to the fungal microbial assembly into house dust. Microbial communities also thrive and contribute to dust and mold due to water seepage, high moisture content, or floods. Besides the fungal R. mucilaginosa culprit, the microbial house dust due to water damage or dampness is also constituted by bacterial communities such as mycobacteria and streptomycetes (8).

A study conducted by Woodcock et al in 2006 on synthetic and feather pillows in UK concludes that if you continue using your pillows and beddings for years and years, the airborne R. mucilaginosa gets accumulated there too (9)! Other common species found in these beddings were Aspergillus fumigatus and Aureobasidium pullulans. It is not difficult to understand by now that these airborne household pathogens exert a regulatory effect on the human health, especially dealing with allergies, gut microbiota, and immune system cross - regulation.

Commercial Significance of Rhodotorula mucilaginosa

Besides being pathogenic and hazardous to human immunity, this fungus is recognized as the one of the top ten causes of food spoilage (10). It has been reported that immunocompromised patients receiving hospital food such as cheese, meet, and fruits have shown contamination of Candida, Trichosporon, Saccharomyces, Rhodotorula, Aureobasidium yeast species (11). This and other opportunistic yeast pathogens have also been found in other foods and beverages such as peanuts, apple cider, cherries, fresh fruits, fruit juice (common pathogens are Candida lambica, Candida sake, and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa), sausages, edible molluscs, and crustaceans (12, 13).

However, these pigmented yeasts have some biotechnological applications too. Some of these are carotenoid production, liquid bioremediation, heavy metal biotransformation, and antifungal and plant growth-promoting functions. The red pigment or the carotenoids serve to protect the yeast from destructive UV irradiation. This was proven by showing greater UV-B protection of the yeast that produced greater number of carotenoids molecules (specifically torularhodin). This phenomenon is referred to as Photoprotection and is a key feature of R. mucilaginosa (14). Therefore, greater the pigmentation produced in the yeast, greater is its survival and resistance towards UV-B. Water treatment using Rhodotorula mucilaginosa is also a promising approach since this fungus is capable of absorbing iron (III) ions from contaminated waters (3).

The Rhodotorula species have also been shown to degrade plastics as seen by their colonization on plasticizers and presence of metabolites from their breakdown (15). It has therefore been implicated in contaminating plastic medical or surgical devices. Their presence has been recorded on plastic catheter devices, bathtubs, toothbrushes, etc. Being cold-adaptive, a marine Antarctic strain of R. mucilaginosa has promising future in showing enhanced extracellular protease production at low temperatures with lower levels of glucose and peptone in the culture media (16).

Xylitol and ethanol production from sugar sources like glucose and galactose have also been implicated to novel R. mucilaginosa yeast strain PTD3 (isolated from the stem of a poplar tree) by a group of scientists from the University of Washington. In fact, this strain produced even higher concentrations of xylitol than the known fungal producer Candida guilliermondii (17).

In another study, two Malaysian R. mucilaginosa isolates, identified by mass spectrometry and 18S rRNA phylogenetic analysis, displayed lactonase activity, which is exploited by the R. mucilaginosa cells to degrade the quorum quenching homoserine lactone molecules (18).

Health Implications of R. mucilaginosa Infections

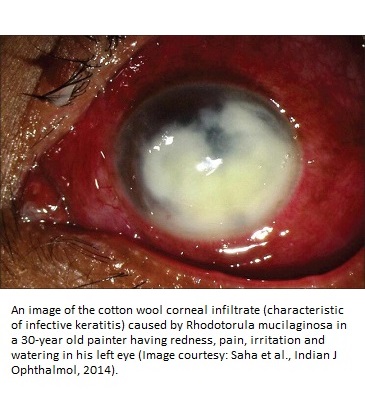

Fungemia is the most common form of infection caused by this species. Second to fungemia, eye infections are most frequently incited by this fungal species. In fact, 79% of the Rhodotorula infections result in fungemia and eye infections. The most common effect of Rhodotorula mucilaginosa eye infections is the loss of vision, keratitis, and endophthalmitis. In a study from Eastern India published in the Indian Journal of Ophthalmology, a case of a 30-year old male was presented, showing presence of fungal hyphae and yeast cells in the smear from his corneal scraping (19). This was a case of acute keratitis in his left eye, identified by redness, irritation, and pain.

Additionally, this pathogen is known to cause cases of meningitis, prosthetic joint infection, oral ulcers, dermatitis (different sorts of skin irritations/infections), peritonitis (inflammation of the abdominal lining), onychomycosis (nail infections), endocarditis (inflammation of the heart lining), and lymphadenitis (lymph gland infections) (10). Immunocompromised patients in intensive care units are also prone to develop systemic infections of Rhodotorula or fungemia.

Interestingly, in a study published in Mycopathologia in 2016, R. mucilaginosa-associated fungemia was identified in an immunocompetent patient having tuberculosis infection of lungs, who responded well to the antifungal amphotericin B (20).

What are the Risk Factors of Developing R. mucilaginosa Infections?

As already mentioned, this fungal pathogen poses the greatest threat to the people with an immunocompromised immune system. People who have undergone catheterization (central venous catheters or umbilical venous catheters) for long periods are primarily at the highest risk for developing Rhodotorula infections.

Various other factors include use of immunosuppression drugs, malignancies of blood, solid tumors, liver and kidney dysfunction, and prolonged use of broad spectrum antibiotics and corticosteroids, sickle cell anemia, and short bowel disease.

Recipients of organ transplants or bone marrow transplants, chemotherapy, or anti retroviral therapy (ART) for HIV-AIDS also face an elevated risk of R. mucilaginosa attack due to extended use of catheters and drugs. If you wish to understand the underlying diseases during coinfection with R. mucilaginosa, I suggest you to read the epidemiologic report by Wirth and Goldani published in 2014 (4).

In 2008, Tuon and Costa from the Department of Infections and Parasitic Diseases, University of São Paulo, Brazil published a review based on 128 cases of Rhodotorula infections. They concluded that out of different species of Rhodotorula, R. mucilaginosa was the most frequently observed and immunosuppression and cancer were the most common risk factors for contracting this infection (21).

Moreover, Rhodotorula infections resulted in roughly 13% mortality among patients.

Treatment Options in Rhodotorula Infections

In case of Rhodotorula fungemia, co-treatment of neutropenia is mandatory. Systemic antifungal treatment may not be necessary and catheter removal may simply be needed to get rid of the virulent Rhodotorula mucilaginosa. When getting rid of catheters is not an option, treatment with amphotericin B is recommended (22).

Systemic eye infections may be treated by oral itriconazole while topical treatments include amphotericin B and natamycin and atropine drops (19). Topical voriconazole may also be considered in unresponsive patients. Overall, we need to change our unprepared attitude towards the infections caused by this rare species of fungi for timely and effective therapeutic success.

To learn how to treat Rhodotorula mucilaginosa naturally click here.

About the Author

Dr. Vibhuti Rana completed her Bachelors's Degree (Bioinformatics Hons.) from Punjab University and accomplished her Master’s Degree (2012) in Genomics with a Gold Medal from Madurai Kamaraj University, India. In 2020, she received her doctorate in Molecular Biology from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research-Institute of Microbial Technology in affiliation with the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India.

Her focus areas include microbial drug resistance, epidemiology, and protein-protein interactions in infectious diseases. As a Molecular Biologist with extensive experience with infectious diseases, we are happy she is part of the YeastInfectionAdvisor team.

Any questions about Rhodotorula mucilaginosa or yeast infections in general, please feel free to contact us from the contact page of this website or see your doctor.

Dr. Rana's Medical References

- Louria DB, Greenberg SM, Molander DW. Fungemia caused by certain nonpathogenic strains of the family Cryptococcaceae. Report of two cases due to Rhodotorula and Torulopsis glabrata. N Engl J Med. 1960 Dec 22;263:1281-4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196012222632504. PMID: 13763698. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13763698/

- William T. Starmer, Marc-André Lachance, in Chapter 6, Yeast Ecology, The Yeasts (Fifth Edition), 2011

- Cudowski, A., Pietryczuk, A. Biochemical response of Rhodotorula mucilaginosa and Cladosporium herbarum isolated from aquatic environment on iron(III) ions. Sci Rep 9, 19492 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56088-5. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-56088-5

- Wirth F, Goldani LZ. Epidemiology of Rhodotorula: an emerging pathogen. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2012;2012:465717. doi:10.1155/2012/465717 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3469092/

- José Paulo Sampaio, in The Yeasts (Fifth Edition), 2011 155.32 Rhodotorula mucilaginosa (Jörgensen) F.C. Harrison (1928)

- Leaw SN, Chang HC, Sun HF, Barton R, Bouchara JP, Chang TC. Identification of medically important yeast species by sequence analysis of the internal transcribed spacer regions [published correction appears in J Clin Microbiol. 2007 Mar;45(3):1079]. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(3):693-699. doi:10.1128/JCM.44.3.693-699.2006 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1393093/

- Kidd et al., Descriptions of Medical Fungi (third edition) 2016. https://mycology.adelaide.edu.au/docs/fungus3-book.pdf

- Shan Y, Wu W, Fan W, Haahtela T, Zhang G. House dust microbiome and human health risks. Int Microbiol. 2019 Sep;22(3):297-304. doi: 10.1007/s10123-019-00057-5. Epub 2019 Jan 14. PMID: 30811000. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30811000/

- Woodcock AA, Steel N, Moore CB, Howard SJ, Custovic A, Denning DW. Fungal contamination of bedding. Allergy. 2006 Jan;61(1):140-2. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00941.x. PMID: 16364170. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16364170/

- J.Albertyn C.H.Pohl B.C.Viljoen Rhodotorula, in Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology (Second Edition), 2014

- Tomsíková A. Riziko houbové infekce z nĕkterých potravin, zvlástĕ pro imunoalterované pacienty [Risk of fungal infection from foods, particularly in immunocompromised patients]. Epidemiol Mikrobiol Imunol. 2002 Apr;51(2):78-81. Czech. PMID: 11987585. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11987585/

- Tournas VH, Heeres J, Burgess L. Moulds and yeasts in fruit salads and fruit juices. Food Microbiol. 2006 Oct;23(7):684-8. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2006.01.003. Epub 2006 Mar 20. PMID: 16943069. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16943069/

- Kajikazawa T, Sugita T, Takashima M, Nishikawa A. Detection of pathogenic yeasts from processed fresh edible sea urchins sold in a fish market. Nihon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi. 2007;48(4):169-72. doi: 10.3314/jjmm.48.169. PMID: 17975532. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17975532/

- Moliné, M et al. "Photoprotection By Carotenoid Pigments in the Yeast Rhodotorula Mucilaginosa: the Role of Torularhodin." Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences, vol. 9, no. 8, 2010, pp. 1145-51. https://pubs.rsc.org/en/Content/ArticleLanding/2010/PP/c0pp00009d#!divAbstract

- Gartshore J, Cooper DG, Nicell JA. Biodegradation of plasticizers by Rhodotorula rubra. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2003 Jun;22(6):1244-51. PMID: 12785580. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12785580/

- Chaud LC, Lario LD, Bonugli-Santos RC, Sette LD, Pessoa Junior A, Felipe MD. Improvement in extracellular protease production by the marine antarctic yeast Rhodotorula mucilaginosa L7. N Biotechnol. 2016 Dec 25;33(6):807-814. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2016.07.016. Epub 2016 Jul 27. PMID: 27474110. . https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27474110/

- Bura R, Vajzovic A, Doty SL. Novel endophytic yeast Rhodotorula mucilaginosa strain PTD3 I: production of xylitol and ethanol. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012 Jul;39(7):1003-11. doi: 10.1007/s10295-012-1109-x. Epub 2012 Mar 8. PMID: 22399239. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22399239/

- Ghani NA, Sulaiman J, Ismail Z, Chan XY, Yin WF, Chan KG. Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, a quorum quenching yeast exhibiting lactonase activity isolated from a tropical shoreline. Sensors (Basel). 2014 Apr 9;14(4):6463-73. doi: 10.3390/s140406463. PMID: 24721765; PMCID: PMC4029656. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24721765/

- Saha S, Sengupta J, Chatterjee D, Banerjee D. Rhodotorula mucilaginosa Keratitis: a rare fungus from Eastern India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(3):341-344. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.111133. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4061676/

- Pereira C, Ribeiro S, Lopes V, Mendonça T. Rhodotorula mucilaginosa Fungemia and Pleural Tuberculosis in an Immunocompetent Patient: An Uncommon Association. Mycopathologia. 2016 Feb;181(1-2):145-9. doi: 10.1007/s11046-015-9942-x. Epub 2015 Sep 14. PMID: 26369644. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26369644/

- Tuon FF, Costa SF. Rhodotorula infection. A systematic review of 128 cases from literature. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2008 Sep 30;25(3):135-40. doi: 10.1016/s1130-1406(08)70032-9. PMID: 18785780. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18785780/

- Anatoliotaki M, Mantadakis E, Galanakis E, Samonis G. Rhodotorula species fungemia: a threat to the immunocompromised host. Clin Lab. 2003;49(1-2):49-55. PMID: 12593475.

Home Privacy Policy Copyright Policy Disclosure Policy Doctors Store

Copyright © 2003 - 2025. All Rights Reserved under USC Title 17. Do not copy

content from the pages of this website without our expressed written consent.

To do so is Plagiarism, Not Fair Use, is Illegal, and a violation of the

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998.