- Home

- Species & Infections

- Candida Lusitaniae

Candida lusitaniae - An Emerging Fungal Pathogen

Updated 6/15/2025

Written by Molecular Biologist Dr. Vibhuti Rana, PhD

Candida lusitaniae is one of the rare or uncommon fungal yeast pathogens that is now gaining importance as an emerging cause of candidemia. Over the last two decades, a number of Candida species other than the conventional Candida albicans have been associated with fungemia in populations across the world. These species include C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei, C. tropicalis, C. guilliermondii, C. rugosa, and C. lusitaniae.

Various non-C. albicans Candida species form a part of the normal body microflora in humans and can be found on the skin, mouth, vagina, or intestines; and are not harmful in healthy hosts as long as their proportions are within control. Overall, the above mentioned Candida yeast species rank within the top five common causes of blood stream infections in hospital settings. This article describes some of the interesting features of C. lusitaniae and how it has transformed from a harmless microbe of the human microflora to a serious etiological agent of infection.

Depending upon the immune strength of the hosts, C. lusitaniae may cause oral thrush, vaginitis (superficial infections); endocarditis, endophthalmitis (deep seated infections of tissues); or single organ fungemia (pulmonary fungemia) and blood stream infections. All these infections are also caused by other Candida species including C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, and C. krusei (1).

In another review of literature and case report published in 2003, it was discussed that fungemia was the main outcome of C. lusitaniae infections; less frequently followed by meningitis, peritonitis, and urinary tract infections. In this study, only 5% death rate was seen and majority of the affected patients had predisposing risk factors and co-existing illnesses, enabling the pathogen to pounce upon the host defenses (2).

Did you know that C. lusitaniae was first isolated in 1959 from the intestines of warm-blooded animals where they form a part of normal microbial population? It has also been associated with environmental sources like fruit juices, and milk from cows with mastitis (3, 4).

In humans, C. lusitaniae was first identified as an opportunistic yeast species in 1979 by Holzschu et al in a patient suffering from leukemia. This group of researchers employed molecular taxonomical and DNA-based techniques for accurate classification of C. lusitaniae (5).

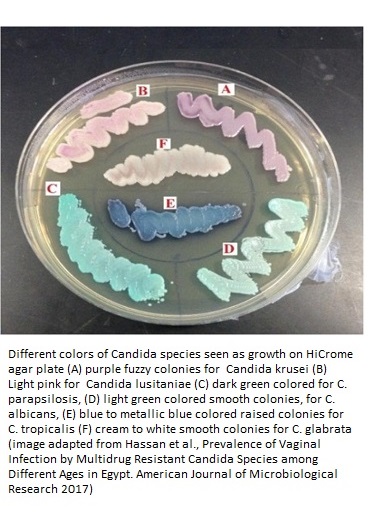

It is also known by a synonym name of Clavispora lusitaniae. The detailed classification of this fungus is Kingdom Fungi, Division Ascomycota, Subphylum Saccharomycotina, Class Saccharomycetes, Order Saccharomycetales, Family Saccharomycetaceae, Genus Candida, and Species C. lusitaniae. Different strains of the C. lusitaniae fungus do not produce true hyphae, instead form pseudohyphae on which the oval/ellipsoidal blastoconidia chains develop by budding. C. lusitaniae produces pinkish-purple colonies on chromogenic agar and may also show waxy texture in appearance.

The intensity, distribution, and kind of infections are dependent on several factors. Some of them are geographical distribution, the clinical strains of the fungi, the policies of antifungal usage in the given country, the patient population, and of course the immune strength of the patients.

In a study lead by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, C. lusitaniae comprised roughly 28% of the total 79 incidents of blood culture infections due to non-C. albicans species. These patients had some or the other hematological malignancies (cancers related to blood) (6). In fact, another study from the MD Anderson Cancer Center showed 25% mortality in 12 patients affected with C. lusitaniae. These patients had multiple underlying comorbidities (solid tumors, bone marrow transplants, and hematologic malignancy).

The combination of fluconazole and amphotericin B was effective only in a few of the neutropenic patients and this study called for other successful alternatives for treating C. lusitaniae infections in immunocompromised hosts (7). Pulmonary or respiratory fungal infections like pleuropulmonary infections, coexisting with bronchiolo-alveolar carcinoma have also been associated with this rare emerging nosocomial fungal infection in past (8).

In case of genitourinary tract infections caused by Candida species, C. lusitaniae contributes to 1.7% of the total cases, mainly in patients with hematological malignancies or those who are receiving chemotherapy (9).

In a study conducted in 160 women in Egypt, chronic recurring vulvovaginal candidiasis (characterized by symptoms including vaginal itching, discomfort and pain, sexual dysfunctions, rashes, and odorless thick, white vaginal discharge) was seen in 100 of the subjects. The C. lusitaniae occurrence was found to be second (13.7%) only to that of C. albicans while the third place was bagged by C. krusei. Unfortunately, these isolates showed resistance to fluconazole, amphotericin B, and ketoconazole and exhibited some effective inhibition up to 65% by Nystatin (10).

How is Candida lusitaniae Infection Acquired?

Not much is known about the epidemiological details of C. lusitaniae and how it attacks the host immune system. However, it is quite well documented that it is a common source of nosocomial (hospital-acquired) infection. Patients receiving bone marrow transplants, blood transfusions, or who are admitted to the Intensive Care Units (ICUs) at tertiary care hospitals are most prone to these infections.

Patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapies, hemodialysis, and use of catheters also presented this infection. These fungal infections are transmitted from patient to patient or through medical devices. Prolonged exposure to antibiotics also contributes to resistant to Candida yeast species and failure of common antifungal therapies (11).

Another very recent study carried out in Kuwait employed DNA based molecular techniques for species identification and has highlighted the emerging role of C. lusitaniae (occurrence of 2%) as a healthcare-associated pathogen, having the ability to cause fungemia or bloodstream related infections in neonatal intensive care unit patients; mainly in preterm neonates. These researchers anticipate that C. lusitaniae can cause a noticeable rate of neonate fatality (12).

Candida lusitaniae Treatment Failure due to Drug Resistance

A number of cases discussing the emerging resistance of C. lusitaniae towards the existing antifungals have come up in literature. This resistance renders the drug of choice useless in severe C. lusitaniae candidemia conditions.

Amphotericin B resistance has been observed in chronic C. lusitaniae candidiasis and leads to treatment failure, e.g., in an ovarian cancer patient with prolonged C. lusitaniae infection (13). In this case, the isolate that was initially susceptible to AmpB transformed and showed resistance after seven weeks of treatment.

Another case report published by Asner et al talks about the multifungal resistance acquired by C. lusitaniae clinical isolate from an immunocompromised young child suffering from acute enterocolitis and visceral adenoviral disease. The patient was undergoing amphotericin B, caspofungin, and azole treatment for chronic and persistent candidemia. The multifungal resistance was seen against echinocandins and azoles due to point mutations in the resistance determining genetic loci like FKS1 hotspot and over expression of the major facilitator efflux pump encoding gene MFS7 (14). Echinocandin resistance due to FKS1 missense mutation has also been observed in other cases during caspofungin treatment (15).

C. lusitaniae has a potential ability to adapt itself to different conditions inside the host cells during the antimycotic therapy. To support this, a major comparative genomics approach was adapted by a group of researchers from the Lausanne University Hospital, Switzerland for studying the multidrug resistance characteristics of C. lusitaniae infections. They reported a number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (point mutations in the coding regions of the C. lusitaniae genome), out of which, six were strongly related to multidrug resistance. The resistance conferring genes included MRR1 (transcriptional activator), MFS7 (multidrug transporter), FKS1 (glucan synthesis gene targeted by candins), and ERG3 and ERG4 (involved in ergosterol biosynthesis and metabolism) (16).

Based on a study conducted in a female patient suffering from post laparoscopy peritoneal infection caused by C. lusitaniae, Wawrysiuk et al concluded that C. lusitaniae generates systemic and local infections similar to other non C. albicans Candida species. It has a unique ability to exhibit amphotericin B resistance (9). Post peritonitis and septicemia death in a patient revealed five strains of C. lusitaniae which showed high levels of amphotericin resistance too (17).

Treatment Conclussion

By now you would have understood that the emergence of uncommon Candida species infections over the last few years have resulted in lesser tolerance to the azole and echinocandin antimycotic drugs. This has ultimately led to high mortality due to candidemia related challenging infections. Species identification using modern molecular and genomics techniques and deciding on the correct antifungal therapy are the key factors for treating infected patients in a rapid and successful manner. It is ultimately surgery that might be the final choice of treatment option in case of peritonitis due to C. lusitaniae infections.

We can also say that prevention is better than cure. Therefore, immunity boosting therapies and diets, which can augment host defenses instead of rendering them vulnerable, are a key area of interest in today’s researchers. Cytokines such as IFN-gamma, combined with antifungal agents, might be a way to boost immunity and is actively being studied for successful implementation in antifungal therapies.

As we know, neutropenic patients are also prone to fungal Candida species infections. Hence, ways to increase the white blood cell count and manipulate neutrophils to enhance their efficiency is another promising area of antifungal treatment. Moreover, recombinant anti-Candida antibody-derived therapies are also being probed for better understanding of these infections and designing suitable treatments (18).

To learn how to treat Candida lusitaniae naturally click here.

About the Author

Dr. Vibhuti Rana completed her Bachelors's Degree (Bioinformatics

Hons.) from Punjab University and accomplished her Master’s Degree

(2012) in Genomics with a Gold Medal from Madurai Kamaraj University,

India. In 2020, she received her doctorate in Molecular Biology from the

Council of Scientific and Industrial Research-Institute of Microbial

Technology in affiliation with the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New

Delhi, India.

Her focus areas include microbial drug

resistance, epidemiology, and protein-protein interactions in infectious

diseases. As a Molecular Biologist with extensive

experience with infectious diseases, we are happy she is part of the YeastInfectionAdvisor team.

Any questions about Candida lusitaniae or about yeast infections in general, please feel free to contact us or see your doctor.

Dr. Rana's Medical References

1. Hommel RK, CANDIDA | Introduction.

Reference Module in Food Science. Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology

(Second Edition), Academic Press, 2014, Pages 367-373.

2. Hawkins JL, Baddour LM. Candida lusitaniae infections in the era of fluconazole availability. Clin Infect Dis. 2003; 36(2):e14-e18. doi:10.1086/344651.

3. Van Uden, N., and H. Buckley. 1970. Candida Berkhout, p. 893-1087. In J. Lodder (ed.), The yeasts. A taxonomic study. North Holland Publishing Co., Amsterdam.

4. Cooper CR, Chapter 2 - Yeasts Pathogenic to Humans. The Yeasts (Fifth Edition). 2011, Pages 9-19

5.

Holzschu DL, Presley HL, Miranda M, Phaff HJ. Identification of Candida

lusitaniae as an opportunistic yeast in humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1979; 10(2):202-205. doi:10.1128/JCM.10.2.202-205.1979.

6.

Jung DS, Farmakiotis D, Jiang Y, Tarrand JJ, Kontoyiannis DP. Uncommon

Candida Species Fungemia among Cancer Patients, Houston, Texas,

USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015; 21(11):1942-1950. doi:10.3201/eid2111.150404.

7. Minari A, Hachem R, Raad I. Candida lusitaniae: a cause of breakthrough fungemia in cancer patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2001; 32(2):186-190. doi:10.1086/318473.

8. Tikotekar A, Naik A, Fisher B, Rahman H, Lopez R. Candida Lusitaniae: An Emerging Cause of Pleuropulmonary Infection. Chest 2008; 134 (4).

9.

Wawrysiuk S, Rechberger T, Futyma K, Miotła P. Candida lusitaniae - a

case report of an intraperitoneal infection. Prz Menopauzalny. 2018; 17(2):94-96. doi:10.5114/pm.2018.77310.

10. Hassan MHA, Ismail MA, & Shoreit AMMAM. (2017).

Prevalence of Vaginal Infection by Multidrug Resistant Candida Species

among Different Ages in Egypt. American Journal of Microbiological

Research, 5(4), 78-85.

11. Sanchez V, Vazquez JA, Barth-Jones D, Dembry L, Sobel JD, Zervos MJ. Epidemiology of nosocomial acquisition of Candida lusitaniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1992; 30(11):3005-3008. doi:10.1128/JCM.30.11.3005-3008.1992.

12. Khan Z, Ahmad S, Al-Sweih N, Khan S, Joseph L (2019) Candida lusitaniae in Kuwait: Prevalence, antifungal susceptibility and role in neonatal fungemia. PLoS ONE 14(3): e0213532.

13.

McClenny NB, Fei H, Baron EJ,. Change in colony morphology of Candida

lusitaniae in association with development of amphotericin B

resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002; 46(5):1325-1328. doi:10.1128/aac.46.5.1325-1328.2002.

14.

Asner SA, Giulieri S, Diezi M, Marchetti O, Sanglard D. Acquired

Multidrug Antifungal Resistance in Candida lusitaniae during

Therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015; 59(12):7715-7722. doi:10.1128/AAC.02204-15.

15.

Desnos-Ollivier M, Moquet O, Chouaki T, Guérin AM, Dromer F.

Development of echinocandin resistance in Clavispora lusitaniae during

caspofungin treatment. J Clin Microbiol. 2011; 49(6):2304-2306. doi:10.1128/JCM.00325-11.

16.

Kannan A, Asner SA, Trachsel E, Kelly S, Parker J, Sanglard D.

Comparative Genomics for the Elucidation of Multidrug Resistance

in Candida lusitaniae. mBio Dec 2019, 10 (6) e02512-19; DOI: 10.1128/mBio.02512-19.

17.

Guinet R, Chanas J, Goullier A, Bonnefoy G, Ambroise-Thomas P. Fatal

septicemia due to amphotericin B-resistant Candida lusitaniae. J Clin

Microbiol. 1983; 18(2):443-444. doi:10.1128/JCM.18.2.443-444.1983.

18. Casadevall A. The third age of antimicrobial therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 42(10):1414-1416. doi:10.1086/503431.

Home Privacy Policy Copyright Policy Disclosure Policy Doctors Store

Copyright © 2003 - 2025. All Rights Reserved under USC Title 17. Do not copy

content from the pages of this website without our expressed written consent.

To do so is Plagiarism, Not Fair Use, is Illegal, and a violation of the

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998.